Small Things

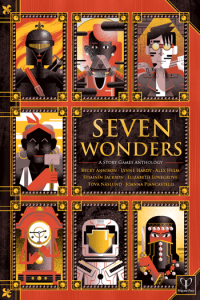

Designed by Lynne Hardy and Published by Pelgrane Press as part of the 7 Wonders Anthology Available at the Pelgrane Press site.

Designed by Lynne Hardy and Published by Pelgrane Press as part of the 7 Wonders Anthology Available at the Pelgrane Press site.

Pelgrane Press has recently published a fantastic anthology of story games, titled “Seven Wonders”. I will be preparing short reviews of all seven games within the book as part of my “Indie Gems” series. The fifth of these is a game by Lynne Hardy, titled “Small Things”.

The introduction begins as follows.

In Small Things you play a noble guardian who protects your House and Family from whatever may come along. Problem is, you’re only little.

The default setting is Britain, somewhere between 1930 and the mid-1950s (but without the inconvenience of a World War and rationing), but you can also set it in your country during the same mythical time period. Small Things takes place in a world of faded colours, good manners, few labour-saving gadgets and tea made in big brown teapots and left on the hearth to warm under a stripy tea cozy.

If games had a smell, this one’s would be like hot buttered toast, newly baked bread and cakes, fresh cut grass and clean laundry. It might look a bit like a Raymond Briggs graphic novel (but much, much cheerier), or Wallace and Gromit without the modern conveniences.

This is one of those games that appears to be simple under the surface, but holds a wicked sharpness underneath. It’s a game where each of the players portrays one of the small being, almost a spirit of the household. They are hidden from the big people, unappreciated for their hard work at keeping a household. They fight valiantly against disrepair, dust, and clutter, which threaten the Family. It seems to be a beautiful metaphor for how feminine-coded labour is treated by society, and it’s masterfully done.

When you begin the game, you collaboratively determine the kind of home, such as a country cottage, a flat, or an old home. You then pick the kind of family which lives there; anything from a big family, to grandparents, to a single bachelor. This combination of home and the family that lives there does a fantastic job of increasing the diversity of potential play experiences, and the kinds of problems they are likely to face. Simple elements combine to create novel situations, and the structure allows for episodic stories as homes or families change.

The resolution system is elegant and thematic. Each of the Small Things has a few special abilities, things like mending cloth, or closing doors. If they want to do something that they have a relevant ability for, they succeed! Otherwise, they need to work together with other Small Things to come up with a creative solution. This structure means that the Small Things are driven together, either to cooperate, or bicker based on their personalities. The Caretaker watches over the whole affair, by introducing wrinkles such as Big Things (people), Creatures, and the malevolent spirits of disrepair from the Outside.

Brew a pot of tea, curl up with a comforter, and enjoy the game!