Every game comes from somewhere; from personal experience, to intellectual puzzles, to something inbetween. Each designer is naturally faced with a question of which element to use as the foundation for their games. This blog post explores three different approaches, with the strengths and weaknesses I have seen in them. These approaches are:

Stalagmite Design: Concentrating on mechanics first.

Stalactite Design: Concentrating on themes first.

Pillar Design: Concentrating specifically on the interaction of mechanics and theme.

Bottom-up, concentrating on mechanics

Mechanics are the foundation of gameplay. Games are, defined by the presence of rules and procedures that guide play. These could be as simple as deciding who gets to speak next, or as complex as a tactical conflict matrix. These mechanical elements inform that actual activities at the gaming table; what to write down, what to say, when to roll dice, or when to play cards. The stalagmite design concentrates on determining how we act, and when we act during play.

Stalagmite game designs are established with an intentional focus on specific mechanics of play. The entire experience of play is fundamentally driven by those systems. This is typically done by concentrating on a resolution mechanism, but other forms of system design can also qualify in this category. Some excellent examples of Stalagmite designs include…

Burning Wheel, with the life path system, volley-based expanded conflict systems, and the well-crafted Artha cycle.

Microscope, with a robust procedure for generating a timeline collaboratively, and detailed procedures to reinforce equal collaboration at the table.

Stalagmite design is a strong at producing verifiable and repeatable play experience at the table. The focus on core activities of play means that there is a great deal of attention spent on the various decisions made by participants, which can make for a robust and consistent game design. It can produce groundbreaking designs that move the craft forward, and support a wide variety of settings.

Stalagmite design has dangers associated with it. I have found that many of these games have a tendency of having fragile themes during play, that can fall flat and feel more like a board-game than an immersive roleplaying experience. The concentration on activities during play means that there is often a reliance on a few individuals to interpret/describe events so that a coherent story emerges from the gameplay activities.

Top-down, concentrating on themes

Roleplaying games are defined by the narratives they produce. These themes inform the assumptions, the politics, and the values of the creators. Strong games are also artistic statements that communicate ideas through play. These could be done through a focus on certain perspectives, constraints on communication, or on specific settings. The Stalactite design concentrates on who acts, where we act, and why we act in play.

Stalactite game designs are established with an intentional focus on themes and messages. The entire experience of play is designed to reinforce the narrative, and to shape the fiction into reinforcing the themes. This is typically done through establishing strong characters, complex relationships, and a rich setting. Some excellent examples of Stalactite design include…

Montsegeur 1244, a game about Cathars under siege who choose to renounce their faith or burn at the stake. This has pregenerated characters, a premade relationship map, and no random factors. The game is intensely focussed on themes of faith, love, and martyrdom.

Posthuman Pathways, my own game about transhumanism, transformation and sacrifice. The entire system is predicated on the fact that players are constantly faced with hard choices and are obliged to sacrifice something important on the wheel of progress.

Stalactite design is strong at producing emotionally compelling and memorable play experiences at the table. The focus on ideas and themes tends to make for a very dramatic narrative, with compelling character dynamics. It can be an excellent tool for making political statements or discussing sensitive subject matter.

The dangers associated with Stalactite design is that it can be very dependent on the players. Everyone in the game needs to have robust improvisational skills, because the mechanics of play tend to be minimal. Participants also have to all be on the same thematic page, as any disconnect can ruin the experience for the group. These games also tend to be short-lived, burning brightly for a single session and fading afterwards.

Middle-out, concentrating on situations

Stalagmite design starts with the mechanics. Stalactite starts with theme. Pillar design is the third path, where the designer intentionally chooses both a core mechanic and a core theme that interact in a specific way. Pillar design is a way of concentrating on the specific situations that you want to encourage with your design. It’s a compromise solution in many ways, neither as thematically driven, nor as mechanically developed compared to the other options.

Pillar game designs are difficult to craft, because of the difficulty in pairing the two disparate elements. In order for a pillar game to be successful, it needs a core mechanic that is engaging that is either reinforcing or intentionally contrasting the theme. A successful pillar game might be a game about the price of violence, where the strongest tools are violent ones. It might instead be a game that gives tools for resolving conflicts in other ways, and rewards those who abstain from violent options.

Some excellent examples of Pillar designs include…

Headspace, a game about technology (normally portrayed as a dehumanizing force) and teamwork (which requires humanity). The game mechanics centre on a piece of technology, known as the Headspace implant that allows people to share skills. When skills are shared, you also share emotional baggage along for ride. If focusses on emotional consequences as characters work together, and learn about each other’s dark pasts.

Red Markets, is a game about capitalism and zombies. It’s a game where you have to keep careful track of your equipment and maintenance costs as the fundamental experience of play. The only way that you can manage those costs are by spending money, which can only be earned by risking your lives by facing the undead hordes. It’s a game about poverty, and the no-win situations it causes. It’s also currently on kickstarter!

Dread may be the strongest of all of the examples of pillar design. It’s a horror game that uses a Jenga tower as the core mechanic. The physical tower provides a strong sense of suspense and anxiety, underpinning the intentional themes of the game.

Pillar design is good at producing games with a memorable experience. They are relatively unique and focused. They are often quite difficult to design, and are relatively rare. It’s an area of design that I believe warrants further exploration, and it is driving my new design work.

I would welcome your thoughts on this article, and the lens through which I am viewing design. Are there any hidden strengths for any of the approaches that I have neglected to mention? Are there downsides not yet identified? My comments are open.

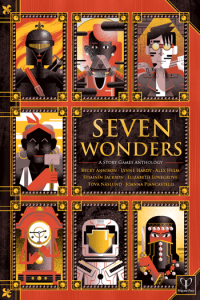

Designed by Stiainín Jackson and Published by Pelgrane Press as part of the 7 Wonders Anthology Available at the Pelgrane Press site.

Designed by Stiainín Jackson and Published by Pelgrane Press as part of the 7 Wonders Anthology Available at the Pelgrane Press site.